Inside Look at Life Behind the Mask During Cincinnati's Coronavirus Pandemic

By CityBeat Staff on Tue, May 5, 2020 at 2:50 pm

The novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19 continues to sweep across the country and, as of April 30, Hamilton County had seen more than 660 confirmed cases resulting in 35 deaths. Nationally, there have been more than 1 million confirmed cases and 63,000 deaths due to COVID-19 in the same time period.

Health experts and public officials have urged precautionary measures, including wearing masks, to slow the spread of the virus. Many Cincinnatians have done so, and it’s a strong recommendation from Gov. Mike DeWine and the Ohio Department of Health to wear one in public as the state moves to slowly reopen businesses.

Some citizens have made their own unique, colorful masks. Others have donned the classic, utilitarian white and blue masks you usually see medical professionals wear.

CityBeat talked to people across a wide array of ages, locations, races and professions who have opted to wear masks about what is foremost on their minds during the historic pandemic. Here are excerpts from those interviews, conducted by Nick Swartsell.

Photos by Nick Swartsell

Scroll down to view images

Nick Swartsell

Kate Zaidan, operator of Dean’s Mediterranean Imports in Findlay Market

“A lot of people who come to Findlay Market seem to be wearing masks. I hear other people say, ‘Oh, I was at other places, and maybe 10 percent of the people have them on.’ I feel like Findlay Market shoppers are a fairly conscientious bunch, and you kind of see that reflected here. I feel like we see maybe 70 to 80 percent of our customers wearing masks. That’s been cool. It’s a good reminder,” Zaidan says.“We walk a fine line between essential and non-essential — you know, we’re a small business, there are other grocery stores available. But we’ve stayed pretty busy. The number of people who use us as a regular grocery store has been striking. People treat this as part of their regular food routine. I feel very happy to be able to be open and keep doing that,” she says.

“My family has been affected in myriad ways. My wife Karen was in school in New York, and as soon as they canceled classes she headed home. But the rate of infection there is so high. I think five out of the 10 people in her program have contracted COVID-19. She found out that the mother-in-law of one of her colleagues died from it. I’m so grateful she is home. And my sister, we’ll maybe never know for sure if she has it, but she’s been sick. She’s not sick enough to get tested, but yeah. It’s been challenging. And then my mom is an RN working at Bethesda North on a COVID floor. She has to be there every day. We’re a family business, and my dad usually works a couple hours a day, but we quarantined him immediately. I worry about him. He’s already immune compromised.”

1 of 15

Nick Swartsell

Lauren Wade, University of Cincinnati Health emergency room nurse

“The problem for most of us here is, because of where we work, we’re very worried about bringing this home to our families. I have a mother-in-law currently going through cancer treatments, so she’s at higher risk. My mom, even though she is also a nurse, she’s older. So that’s a concern. It’s a concern for all of us. Of course, we take so many precautions. Nurses are very well protected. We have plenty of PPE. The hospital has taken plenty of steps to make sure that we have what we need and that we don’t get exposed. But it’s still a fear, of course. No matter how many steps you take, we’re all human,” Wade says.“It’s a quick turnaround down here. Because the test takes so long, we don’t usually get to know if someone is positive. But we do see a lot of people we suspect have it. They’re separated from other emergency room complaints, so that people experiencing stroke or heart attack symptoms or anything like that are still safe to come to the hospital without having to worry about being exposed to the virus. At the door, we’re screening for any kind of COVID symptoms, and they go right to the designated area for that.”

“The talk of reopening is a little concerning, that even though we’re slow now, once the state starts to open up, we could start to get a lot busier. Ideally, a lot of us hope that the slow process of reopening will mean a slow trickle of new cases here. But there’s the fear that there could be a big surge all at once. That’s what they’re seeing in other states. The governor here and in Kentucky seem to have done a really good job of planning, though, so hopefully that won’t be the case,” Wade says.

“It’s a shame that sometimes people think that essential workers are only nurses and doctors. There are so many other people still going to work every day and possibly getting exposed to this virus. I hope people will realize that it’s not just people who work in hospitals. They’re not the only important ones. Places that aren’t health care related, I just can’t even imagine. It must be scary for them. They may not be trained on wearing PPE. They may not have the actual resources that a healthcare facility does. I would probably feel safer here than working at a grocery store or doing food delivery. This is what we plan for.”

2 of 15

Nick Swartsell

Trenia Crawford, health care worker

“I’m in health care. I just came from taking care of a female with MRDD disabilities and another female recovering from surgery. It’s been more stressful during this time, for me and for the clients. I try to make my clients as comfortable as possible during the pandemic. I try to stay busy. It keeps me balanced as well,” Crawford says.“I’ve been wearing the mask for a couple weeks. It’s a very uncomfortable adjustment; it makes it hard to breathe and fogs your glasses up. I’m just trying to take it day by day, go with the ebb and flow of it. What can we do other than take the precautions that we’ve been guided to take and be as healthy and safe for ourselves as possible so we don’t take anything to our families? We’re still here and still blessed, we still have this chance to continue on in our lives. That’s what I’m choosing to do.”

3 of 15

Nick Swartsell

Chris Seelbach, Cincinnati City Council member

“What’s been on my mind the most is the city’s budget. If the federal government doesn’t include us in a bailout, the cuts to the city’s budget will be devastating. We will be closing entire parks, rec centers, health centers. From a citywide perspective, I’m incredibly concerned,” Seelbach says.“No one in my family is sick. My CycleBar instructor’s wife has been in the hospital on a ventilator since mid-March. That’s like the closest connection. She was seven-and-a-half months pregnant. While she was in a coma, they did a cesarean section. But they think she’s going to survive. It’s crazy how for some people, it’s just another cold, and for others, it can kill you.”

4 of 15

Nick Swartsell

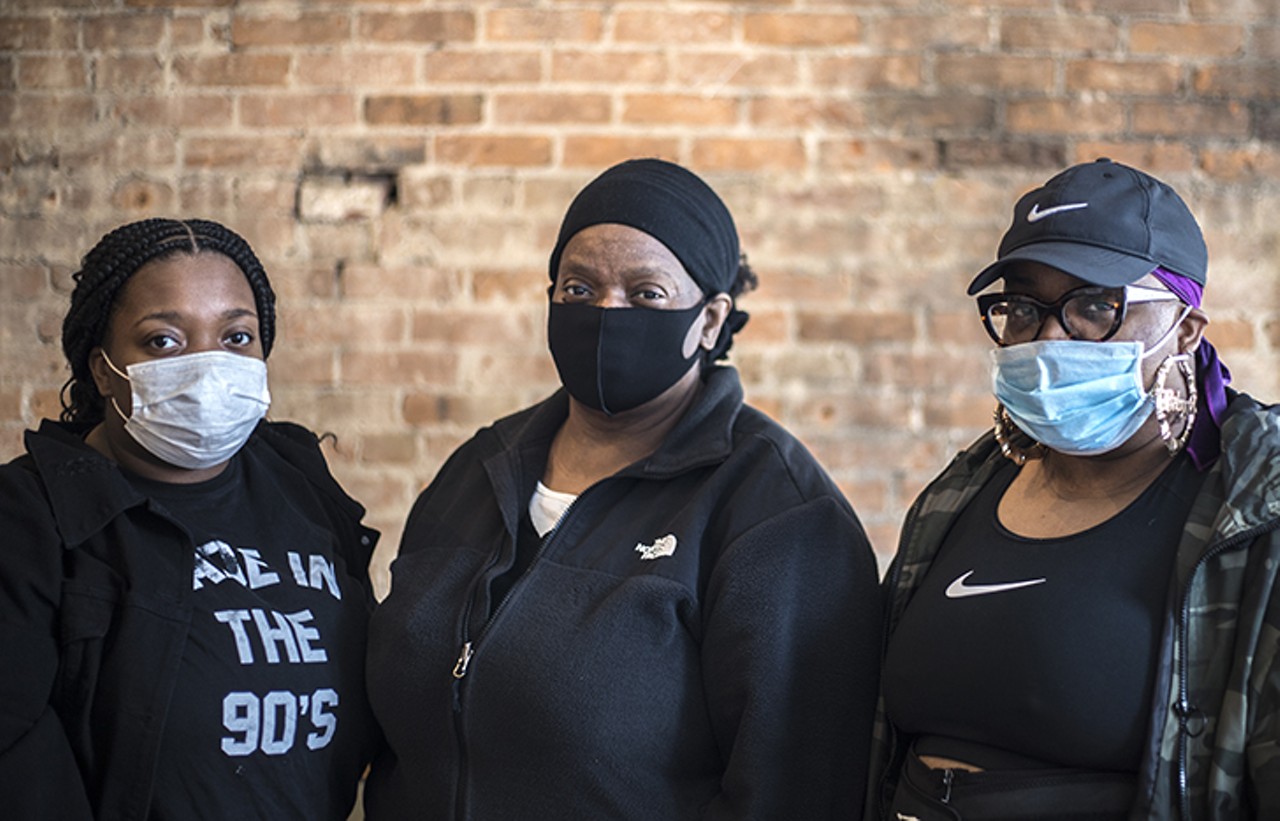

(R to L): Brittany Pitts, Darlene Lamb, Brea Lamb

Brittany Pitts: “I work for Kroger, in customer service. I’m essential.” (Laughs) “I do check cashing and bill payment, so I’m in close contact with people all day. It’s scary, because I deal with a lot of people, and people are still coming to the grocery store. Of course people need food, but I see people coming in every day. It’s become the local hangout. It’s pretty scary. I wish people would stay home and only come out for what they need.”Darlene Lamb: “I’ve been wearing it ever since it started. It’s kinda irritating, but we have to wear them. I’m kind of scared to go out much, because they say stay in as much as you can.”

Brea Lamb: “I’ve been wearing the mask for a couple weeks. But I work from home so I don’t have to wear them too often...Even if they do reopen starting May 1, how are they going to go about that? How do we know it’s safe to be out? Things can be open, but will it be safe for us to go places?”

5 of 15

Nick Swartsell

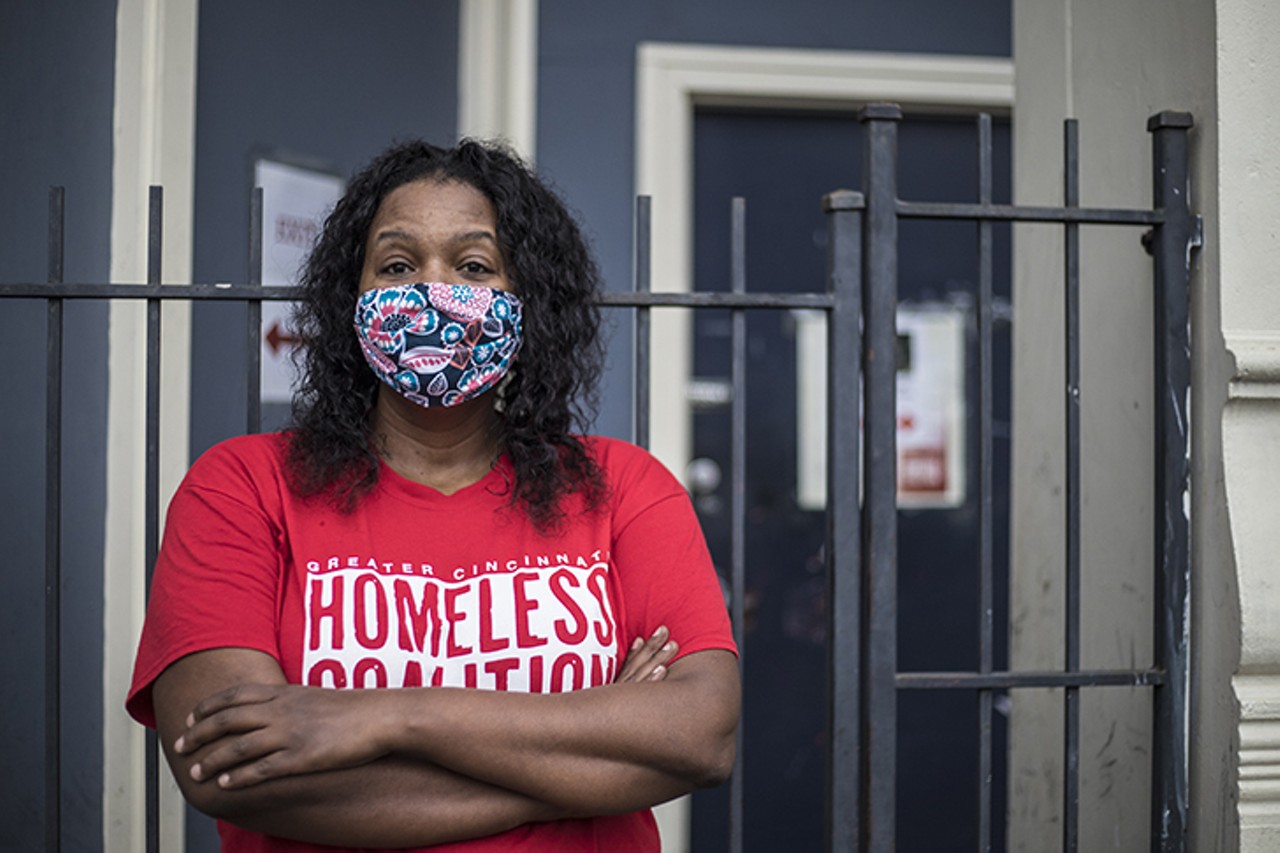

Mona Jenkins, director of Development and Operations for the Greater Cincinnati Homeless Coalition

“We’re seeing more people who are now experiencing homelessness. A lot of people were couch surfing and people they were staying with have said, ‘You’ve got to go.’ Plus Hamilton County released more than 400 people from the jail. Where are most of them going to go? The streets. I live downtown, and I look out my windows and see people walking with their bags,” Jenkins says.“This whole pandemic has pushed a reset button where folks should be understanding just how vulnerable peoples’ situations could be. It was only one week in that people were seeking unemployment, food, all of that. We claim, ‘We’re all in this together.’ Well, let it not be just through the pandemic. Hopefully people understand that the giving and support can’t stop for those in vulnerable work situations and people experiencing homelessness or on the verge of it. I hope people come out with a new perspective on these things that are affecting us. We need to look at some of the policies we have and see how we can change them.”

6 of 15

Nick Swartsell

Molly Sullivan and Peyton Dabney Copes, musicians

Molly Sullivan: “I thought at first that I would be more productive making music. But I have so much of an emotional relationship with music that I couldn’t go there for a while. So I was trying baking. It requires a lot of patience, eats up a lot of time. And the results are, most of the time, pretty good (laughs). We’ve been making crafts for people. Playing board games. I feel incredibly fortunate right now," Sullivan says."The one thing that is probably the most unsettling about all of this to me is that we’re cooped up in these little bubbles with the limited exposure to other people. I think that can be really dangerous. The thoughts we manufacture, based on our prescribed social media feed or whatever… that’s not the total reality. I think it’s probably pretty wise to try to diversify who you’re talking to, to try to get an understanding of the collective experience on the whole. If you’re not out and participating in different sectors of the world, you just don’t see and you aren’t able to even imagine what other peoples’ realities are like.”

Peyton Dabney Copes: “I’m indefinitely unemployed, because I work in music and touring. Certain bands are saying October it’s going to start happening again, but obviously it’s not their call and who knows what is actually going to happen? After the first few weeks I stopped trying to watch the news morning, noon and night. Maybe checking every other day or so instead. There’s only so much you can do," Copes says.

"I’m one of the many in the boat that is trying to apply for unemployment. It’s really unclear what’s going on in that department. I’m trying to not check it every day or stress out about it. It’s out of my hands and I’m one of millions in line and I’m fortunate enough to where if it didn’t happen, I would survive. But if it did happen, it would help out a ton. I’m trying to have a lot of patience with the world and the people I’m close to, because we’re closer than ever. I want to have more patience with everything, really. We’re definitely very fortunate in that we’re obviously not experiencing anything remotely close to what most of the population is dealing with.”

7 of 15

Nick Swartsell

Jennifer Hester, Christ Hospital palliative care advanced practice nurse

“Palliative care is specialized medical care for patients with a serious illness. We focus on relieving pain — physical, emotional, spiritual — associated with serious illness," Hester says. “We typically deal with serious illnesses like cancer and heart failure. Now we’re dealing with an infectious disease, so families are often infected together. There’s an emotional component (with COVID-19) where it feels unnatural and different than the other diseases we address. I think the separation from families at a really hard time is the toughest thing. You’re having critical conversations about where you’re going next in your medical care. Doing that by yourself is a really hard place to be.”“Especially in the beginning for us, the unknown was the most difficult thing. We’re communicating with colleagues nationally, like in New York, who are running out of resources and thinking what if that happens to us? We necessarily had to go to a really dark place to imagine the worst case scenario. We didn’t know if we would be able to flatten the curve in Ohio. What if we run out of medications? What if we run out of PPE? So we had to get creative really fast. But we were blessed with time and a state and local government and hospital system that did a really good job flattening the curve. But that unknown is scary for our patients and is scary for us. People in other hospitals have lost colleagues, have lost family members. Could that be coming for us? Could we expose our families? Now it feels like we know a little bit more what we’re doing. We’ve rapidly put processes in place and we feel a little more ready.”

“If you’ve not seen someone really sick with COVID, it’s easy to think, ‘Oh, we’re fine, this is all overblown.’ It feels that way because we did it right. My worry is that people get a little sense of security and think we can go back to normal. I don’t think there’s a normal for a while. There’s a new normal. It is very real, and that can be lost on people who aren’t working in a situation where you’re seeing it.”

“Just watching really smart people work really well together makes me feel like, oh, we really can do this. And I also see that out in my community. We agree that this is how we’re living now. We’re all in this together. I know there is a lot of division, but I’ve also seen a lot of people trying to keep each other safe.”

8 of 15

Nick Swartsell

Jamie Beiser, Rhinegiest employee

“Early on, I was filled with a kind of depression and anxiety, which I’d never really had before. But once I started getting into a new normal flow of how things were happening, it started being a little less intense.” Beiser says a steady stream of orders from grocery stores, individual pickup and delivery orders and establishments that haven’t shuttered have driven enough business to the brewery to keep him working, albeit 32 hours a week instead of 40. “That’s 16 hours a check that I’m missing,” he says. “But we can deal with that. We can figure that out.”As much as the money, he says, it’s about continuing to feel like a part of something bigger. “It’s weird because I don’t consider myself essential,” he says. “There are so many folks who are out there literally saving lives. But it’s cool that I still get to come in and work and be able to represent my city and do things that are helping people in some capacity at least. I’m definitely glad that I can be here.”

9 of 15

Nick Swartsell

Jerry Davis, janitorial worker, Streetvibes contributing writer and vendor

“I can’t sell Streetvibes right now, and I had to leave work for a bit. I was having breathing issues there, and I had to stay in the hospital for a day. They told me I wasn’t in any shape to go to work. I went to a clinic and they told me I have COPD. Work told me they can’t let me come back with everything going on. They just said, we can’t let you come back,” Davis says.“I’m used to working. Now I have to sit around the house and watch movies, maybe drink a beer. There’s nothing else to do. If I went to work and something happened to me, it’d be on them. I’m not getting paid in the meantime,” he says.

“People are waiting on their stimulus checks. I haven’t gotten mine yet, but I’m hoping it comes soon.”

10 of 15

Nick Swartsell

Mark Samaan, Metro Bus Service Planner

“I’ve been viewing it from a transportation standpoint. I’ve still been coming to work every day. I’m a service planner for Metro, so we get the bus ridership every day — who has been riding what buses and where and when. I’m seeing how many people have actually still been riding the bus, which is more than I thought there would be. I expected an 80 or 90 percent decrease. It’s been more like 60. Here, the vast majority of our riders are people who don’t have any other way to get around. The only reason people aren’t riding is because their work is shut down. So when it opens back up, they’ll be riding the bus again. So we’ll have to do things to increase our frequencies to keep maximum (number of riders per bus) down, monitoring to see how long buses have been out so we can keep them clean, that kind of thing,” Samaan says.“I really only have my parents here, and my dad’s parents who live in Oakley. They’re in their 80s and they haven’t left their apartment at all since March. So my dad has been getting all their stuff and leaving it there. They’re being very careful about it. They don’t work. They don’t drive. But they’re like, the happiest people ever right now. They grew up in the old country — Syria — where this is nothing. They grew up post-World War II, when it was just military coup after military coup.”

11 of 15

Nick Swartsell

Alicia Boards, mother and PhD student, and her daughters Addisyn (6) and Alivyah(15)

“They haven’t been out since this happened,” Boards says of her daughters. “Alivyah has asthma. I’m not risking it. I’ve read that a lot of the young people who are dying are due to asthma.” “I have two very different kids. She (Alivyah) is very content being at home. But Addy is my social butterfly, so I get more worried about what it’s going to do long term. It’s very different for her and I’m seeing signs of anxiety I haven’t seen before. Plus, I think it’s very important for them both to be around their peers. It’s hard to be mom, friend, and mediator between the two all at the same time.”“My mom passed away two years ago. She was my biggest support, she lived with us and helped here. Their father’s side of the family isn’t involved. So we just have my dad, and we haven’t seen him since this all started. He’s in Georgetown, Kentucky. We’ve been trying to stay away from him because I couldn’t live with myself if something happened and we brought the virus to him. I order his groceries and pay his bills, try to take care of his household from afar, plus mine. We don’t really have family here otherwise. It’s just us.”

“I still feel privileged because I am in school full time. I get my school stipend. So we’re still here, our bills are still paid. I’m thankful," she says.

“We multitask all the time and often put our families last. Now we get to put our families first, which is nice. People are coming together in some ways, helping each other, sharing food. It’s bringing little pieces of humanity back to us that we didn’t see before because we never slowed down enough. That’s one of the biggest things that I’ve seen so far.”

12 of 15

Nick Swartsell

Reginald Harris, director of Community Life for The Community Builders

“I work for the Community Builders. We’re a nonprofit real estate development company. We have 320 units of rental housing in Avondale and also did the Avondale Town Center. As an affordable housing provider, our first and foremost on our mind is folks being able to stay in their homes. We’ve been working intensely on all types of measures and interventions so people can pay their rent and stay in their homes. We just don’t want people in this time to be out on the streets,” Harris says.“I never want to pathologize neighborhoods and identify them just through their deficits, but I also want to acknowledge the reality that Avondale, for a number of reasons, deals with a number of deficits. So when I watch folks in that community navigate a pandemic, there are different factors at play. People have to make really tough choices. I think about the role that luck and income play. You can’t extract this moment in time from larger sociopolitical issues. The ability of someone to endure this pandemic is directly related to their relationship to healthcare, to education, to employment, to stable housing. When those are unstable, it’s virtually impossible to weather a time that tests the limit of those very things. This magnifies all those issues.”

“I’m thinking about what is considered ‘essential’ and ‘nonessential.’ We can run the risk of devaluing some labor — people who work in grocery stores, people who provide basic services. And as it turns out, in a pandemic like COVID-19, the world absolutely does not function without those roles. As a community, as nation, as a city, we have to reevaluate our relationship to labor and to what we value in terms of jobs," he adds.

“Me personally, I’m pretty scared of this thing. I’ve known several people who are young and healthy in New York, Phoenix, who contracted COVID-19 and they were really sick. Really sick. I had five cousins in Chicago who got a COVID-19 diagnosis. My mom is immunocompromised. She’s taking it very seriously. So my husband and I have been working from home, practicing social distancing, we’ll walk past people on the sidewalk by going into the street. It’s very important to us.”

“I miss going to my barber. Not because I just miss getting a haircut, but because it’s a visceral experience. There’s a proximity that you have. I went to my barber once a week, so he knows me. He knows my face. He knows where I’m at when I come in.”

13 of 15

Nick Swartsell

The Bowers Family — Jared, Lydia, Sammie and Harrison

Jared: “I’m fortunate that I get to work from home. The company I work for has been taking this seriously. I’m a communications specialist. I write internal communications for a financial technology company. I like my commute a hell of a lot more now (laughs). There’s a lot that I like about working from home and I’d do it permanently if I could.”“We’re dealing with all of this stuff on a day-to-day basis and making all of these weird plans for the future. But it seems like we don’t want to accept the fact that no one knows what that future is. Why are we trying to bend this thing to our own timeline? It doesn’t make any sense. This pandemic is a literal force of nature, and we’re like, ‘We’ve gotta get this thing rolling. May 1st!’ Today, this week, that’s what has been causing me a lot of anxiety. Numbers keep going up in terms of infections and deaths, nationwide and in the state. But then there’s this push to open everything back up.”

Lydia: “The first time I went to the grocery I almost cried in the aisles. Our pharmacy is in Target. We have to go in to pick up medication. The whole atmosphere is different. The anxiety and the tension just sits on you. You can tell the people who have to work there are on edge. But you can also tell who doesn’t care — people who think it’s a hoax or something. It almost feels like you can’t look at each other. It’s weird.”

“Just the unknown is hard. At one point they thought what, like 25 percent of people were asymptomatic. Then they thought it was like, 60 percent. And in some jails it’s been even higher? It’s like playing roulette. I don’t know what surface someone has touched. There’s an elevated awareness.”

14 of 15

Nick Swartsell

Tiffany Neri, Brighton Center rapid rehousing specialist (center) and Madison Smith, Brighton Center family support coordinator (far left)

Tiffany Neri: “It’s tough. We’re seeing a lot more need as far as people needing shelter. A lot more need as far as people needing resources to pay their bills. A lot more need for people to get connected to unemployment, or figuring out how to get their stimulus checks. The first few weeks we were out here, we were seeing 70 to 100 households a day. That’s 300 percent more a day than we were serving out of our building before this. And we’re not getting as much food from the stores that usually donate, because of course people are panic buying more. But we have enough food. It’s good — for the first few weeks I wasn’t sure if we would have enough. But we do. It may not be everything people want, but it’s healthy nutritious food,” Neri says. “We’re seeing a lot of people who have lost jobs, or are taking care of other people, or their kids are home and they can’t afford childcare or childcare places aren’t open.”“The biggest thing for me is not getting sick. I can’t get sick. I have too many people around me. Not just the people I’m serving, but the staff around me. I don’t want to get any of them sick. My husband has conditions that can make the illness a lot worse for him. So he’s staying in a separate place. So I’m living by myself. It’s really hard. But here at work, these are the people I depend on. And they depend on me. We’re trying to keep everyone safe and healthy. We check in with everyone a lot, make sure we’re trusting each other, trying to see what each other needs. I’m really, really fortunate in that way.”

Madison Smith: “We’re getting tons of calls about rent, paying utility bills, things like that. The things that are making things a little easier for families right now — the discontinuance of evictions for nonpayment of rent — it’s like a light switch. It’s going to turn back on eventually, and at that point, people are going to be hundreds and hundreds of dollars in debt to their landlords and could face eviction at that point. So people are being really proactive and reaching out to community resources," Smith says. "We’ve gotten some funds from the United Way to bridge some of that gap and meet some of those needs. We’ve been able to help between 75 and 100 families with rents and utilities. CAC, the Community Action Commission down here, got a ton of funding for the whole region now. So hopefully we’re a stop-gap measure and we can get back to what we’re used to doing, which is case management and working with families more in-depth.”

“We’re seeing a 60 percent increase in people who haven’t accessed services in the past three or four years or first-timers who have never accessed services. That really points to the precariousness — people who make just enough income to get by and don’t access services, and then that goes away. They were making just enough to squeak by, and now that’s gone.”

“All the things we assume could never change did sort of change in an instant. I think that frees up peoples’ minds to think of things differently. I hope we come out in a situation where there is that opportunity to be creative and feel like there’s a possibility for change. People sometimes see these barriers as insoluble. This is an opportunity to see that we’re making things up as we go — the things that seem like barriers today may not be tomorrow.”

15 of 15

- Local Cincinnati

- News & Opinion

- Arts & Culture

- Things to Do

- Food & Drink

- Music

- Cincinnati in Pictures

- About City Beat

- About Us

- Advertise

- Contact Us

- Work Here

- Big Lou Holdings, LLC

- Cincinnati CityBeat

- Detroit Metro Times

- Louisville LEO Weekly

- St. Louis Riverfront Times

- Sauce Magazine